Small CI for a small blog

Photo by Collab Media on Unsplash

I haven't written in the blog for a long time, it's time to fix that.

And so recently I finally got around to writing a CI/CD process for automatically rolling out new articles on adult topics through the version control system.

Let's see what came of it.

A blog can be viewed as a product, and each new article as an improvement and a new version.

If we consider the canonical representation of the CI(continuous integration) process [1], as in the figure above, then we can identify the following steps:

Commit - confirming that the system is operational at a technical level. At this stage, the application is compiled and runs through a set of automated tests. In addition, code analysis is performed at this stage.

Auto tests and Performance tests - confirming that the system works at the functional and non-functional levels. At this stage, it is also checked whether the system behavior meets the needs of users and the requirements of the specification.

Manual tests - research and testing are carried out, the usability of the application is assessed, the appearance and behavior of the system on various platforms is checked.

Release - delivering the system to users as a packaged application or by deploying it to production and debug environments.

Below we'll cover all of these steps, excluding automated tests, and how to use them to deploy a blog.

Commit

The commit phase begins with a change in the project state that is committed to the version control system and ends with a bug report or, if the phase is successfully completed, the creation of a set of binary artifacts and deployable builds that are used in subsequent testing and delivery phases of the release.

—Jez Humble and David Farley

Git as a distributed version control system has long since established itself as the best system and a survey conducted back in 2014 on habr already then showed usage statistics of over 70%, so the choice of a version control system was obvious.

The largest web service at the moment GitHub was chosen as a hosting for git repositories, here are some reasons for the choice:

Codespaces lets you start coding faster with fully configured and secure cloud development environments built into GitHub.

Issues Create issues, break them down into tasks, track relationships, add custom fields, and lead discussions.

Code Review Every pull request has lightweight code review tools built into it.

GitHub Actions simplifies automation of all software workflows. Create, test, and deploy your code directly from GitHub.

So, we figured out how to store the code, but what kind of code will it be? Searching for tools led me to the project Nikola — Static Site Generator, several features of the tool:

Generate static HTML content: Static websites are safer, use fewer resources, and avoid vendor and platform lock-in. You can host a Nikola website on any web server, big or small. It's just a bunch of HTML files and data.

Fast and incremental builds: Nikola is fast. It uses doit, which provides incremental builds - in other words, it only rebuilds the pages that need it.

Multiple format support: reStructuredText, Markdown, IPython (Jupyter) Notebooks, and HTML are supported initially, and plugins are available for many other formats.

Built-in components: Nikola comes with everything you need to create a modern website: a blog (with comments, tags, categories, archives, RSS/Atom feeds), easy-to-use image galleries and code listings.

Multi-language support: You can write posts in multiple languages and have links between different versions of the post.

CLI available: allows you to create projects, templates for new posts and pages.

Built-in web server.

As mentioned above, as an output artifact we get static HTML code, which we can then use both as a release and in a test environment. There is no point in storing this artifact separately, since its assembly does not take much time and computing resources, so I perform data assembly directly when creating the stand.

This solution has a number of pros and cons.

+ The speed of assembly is achieved due to previously collected data.

+ Reduced computing resource usage

+ There is no need to store data and control its cleaning.

- When you delete page files, the pages and data collected before deletion remain.

As a source, I chose the reStructuredText format. A huge plus is that, unlike Markdown, it has an extended syntax. But there is also a huge minus: the syntax has to be remembered every time if you rarely use it.

So, to summarize, we have a tool called Nikola to create a blog from code, and that code is stored in our version control system. Next, we put together a build pipeline.

The test and production environments should be as close and reproducible as possible. Therefore, we will launch in a container, a number of advantages:

Configuration is stored in the code

Can be run locally

Fast build if there is a cache

Runs on any modern Linux OS

Isolated environment from the host system

We will launch containers through the docker compose utility, using environment variables, we can create both production and test environments.

The environment is created, let's start testing:

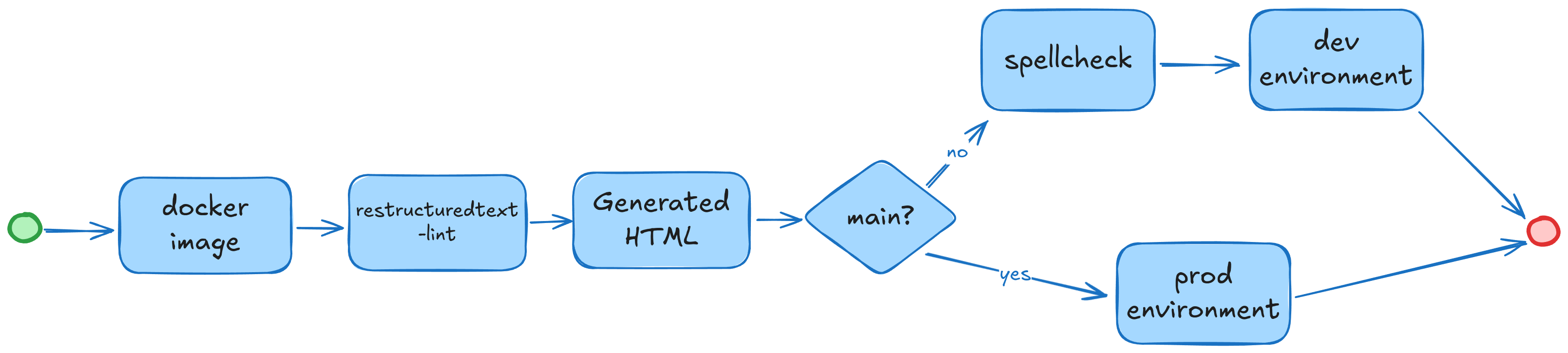

Building the environment, since a new version can be not only the addition of a new post, but also an update of the environment itself, we must be completely sure that it is built.

Running linters, since our source data is stored in reStructuredText, it is advisable to check its syntax before building, for this we will use the restructuredtext-lint package, which allows us to quickly check our code for syntax errors.

Building static content, at this stage we will receive the generated HTML content, or learn about a build error.

Well, since our product is a blog, we check the spelling. After much research, the best results for working with the Russian language were shown by the pyspelling package in conjunction with hunspell.

Now, to avoid confusion in the order of the steps, let's combine them. Here I found it appropriate to use the GNU make tool, it looks simpler than a bash script, and due to target and dependencies you can form usage scenarios, so we have the following:

build - Build environment, linters, static data assembly

test - Run spell checker

start - Run application

stop - Stop application

console - Additional target for diagnosing application operation in the environment.

Also in Makefile we define the current state and parameters of the environment, and if it is the main branch of the version control system then this tells us that we need to start the production environment, and if the branch does not correspond to main then the test one.

Manual testing

And now the article is written, it's time to create a Pull Request in the version control system for the main branch. And this is where the CI process will start, which will prepare a test environment for us, which we can see with our own eyes.

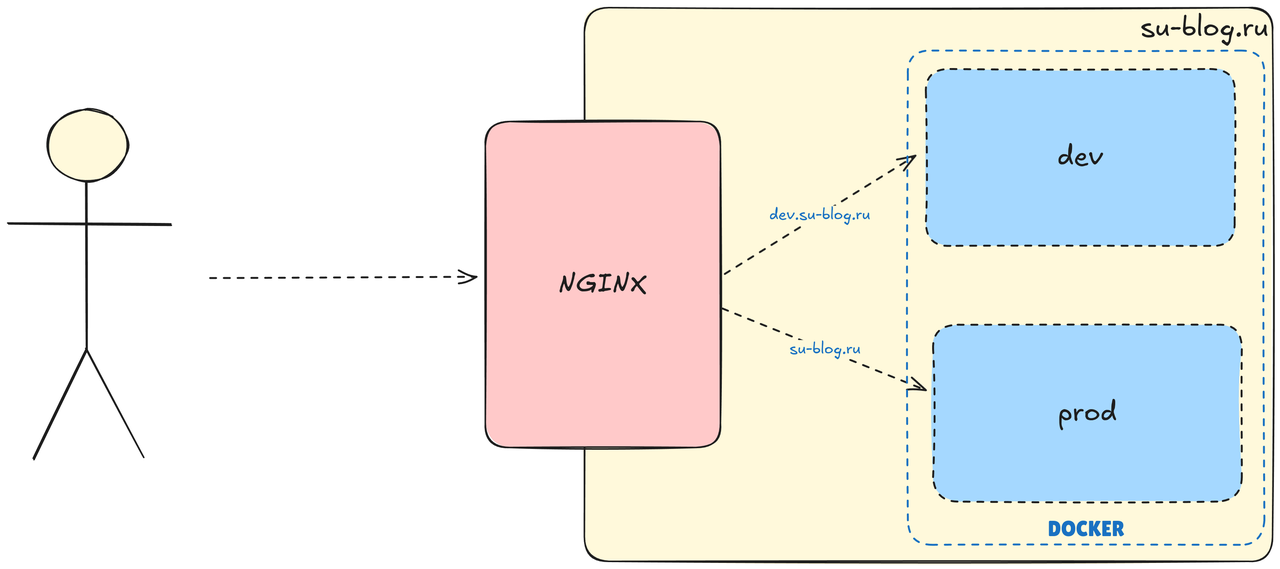

In The GitHub project has prepared self-hosted runners, one for each test and production environment. GitHub Actions, upon catching a pull request from the main branch, will run a task to create the environment in the test environment.

The test environment will be launched in a separate Docker container and will be accessible through a separate domain name dev.su-blog.ru

Once you have verified the display and functionality, you can proceed to merging into the main branch.

Release

As soon as a new commit appears in the main branch, the production environment update will be triggered. The only difference from creating a test environment is that the launch occurs on a separate self-hosted runner, the environment parameters are generated automatically based on the version control system branch.

Conclusions

I didn't want to be a shoemaker without shoes, and this prompted me to put together a small but functional conveyor belt for the blog.

Schematically it looks like this now.